By Carl H. Larsen

It could be the most famous gavel in American political history. Drawing the attention of millions around the world, its commanding slap 50 years ago during the Watergate hearings signaled a constitutional crisis that ultimately would lead to the downfall of a president and raise questions on the allowed scope of presidential power, a theme still being played out today.

I was admiring this carved piece of wood in the Senator Sam J. Ervin Jr. Library and Museum, a series of rooms next to the student library of the Western Piedmont Community College in Morganton, North Carolina. Today Ervin remains the biggest hero of the small county seat, his hometown and where he was known as just "Senator Sam." Americans treasured his folksy style and engaging wit. Said his colleague, Sen. Howard Baker: "The chairman is fond of pointing out from time to time that he is just a country lawyer. He omits to say that he graduated from Harvard Law School with honors."

Visitors might wonder if they're lost as they navigate through the student library bookshelves and look for a librarian. Off to one side is a large wooden desk and comfortable leather chair, seemingly out of place. This was the desk from Ervin's Senate office, placed in front of the entrance to the small museum. "Go ahead, have a seat," I was told, and I soon found myself leaning back in the chair and picking up the vintage telephone to say, "Tell Nixon we need those tapes!"

The head librarian led me into the three Ervin rooms. Just sign in, no tickets needed. As I poked around, she offered a quick refresher course on the who's who of Watergate.

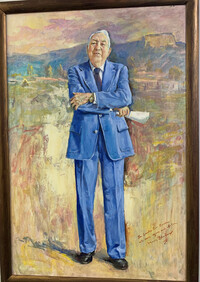

The gavel, with its colorful braided handle, had been a gift from a band of Cherokees to a man who fancied himself just a simple country lawyer but who became a towering figure during a long political career that took him from the North Carolina statehouse to the bench of that state's supreme court — and finally to the corridors of power on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C.

Photos were everywhere, as well as invitations to presidential inaugurations and other mementos — including humorous Watergate items — of a Senate career that lasted from 1954 to 1974. Hanging on the wall was a collection of cartoons about Watergate, many signed by the cartoonists and presented to Ervin.

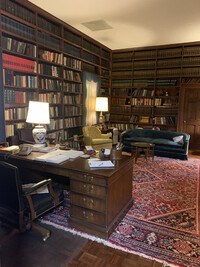

In one room the library from Ervin's nearby Morganton home has been faithfully rebuilt, including furnishings and bookshelves. Ervin died in 1985 at age 88 and is buried in Morganton.

It was 50 years ago, on May 17, 1973, at 10:02 a.m. that Ervin, then 76, wielded the famous gavel and called the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, better known as the Watergate Committee, to order. For weeks the nation was transfixed by gavel-to-gavel TV coverage of the testimony and by Ervin's adept and witty leadership that guided the committee's four Democrat and three Republican senators.

The Senate established the bipartisan committee in the wake of the break-in at the Democratic National Headquarters in June 1972. The burglars had been rounded up and charged, but something wasn't right. Federal Judge John J. Sirica felt that there was more to the story than its being just a routine burglary. Pressing that notion was the dogged reporting by two Washington Post reporters — Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, who developed connections between the burglars and the committee to reelect Nixon as president, a race he handily won in November 1972. On one wall of the museum is a photo given to Ervin by Bernstein.

As revelations of White House involvement were drawn out from committee witnesses, Nixon's popularity plummeted while Ervin's rose. Federal Judge Lawrence M. Baskir remarked that the senator was able "to appeal to the jury" — the jury being the rest of the Senate, the American people and the media. "He knew how to play to them."

Ervin remains an American hero for exposing a threat to the nation's democracy that led to Nixon's resignation. He had had practice, long before Watergate, when he was appointed as a recent arrival to the Senate to a committee that censured Wisconsin Sen. Joseph McCarthy for his blatant misconduct that ruined the professional lives of many. So, Senator Sam also had a leading role in another pivotal case that also ended a threat to democratic values.

And that would be a nice ending. But history hardly ever is cut and dried.

During his career Ervin fought fervently against civil rights legislation going back to the Little Rock school desegregation case, Brown vs. Board of Education and, in retirement, the Equal Rights Amendment. His opposition was cast in his strict interpretations of the Constitution and his belief in what he viewed as individual rights.

The Ervin story — pluses and minuses—is all brought back here. More than a "get out and stretch" stop on a highway amid the beautiful Piedmont country of North Carolina, it recalls an important part of American history.

WHEN YOU GO

www.samervin.wpcc.edu

Carl Larsen is a freelance writer. To read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com.

View Comments