By Sharon Whitley Larsen

"Hut!"

The voice behind us gave the command to change the paddle to the other side of the canoe. Fifteen strokes each time, and then switch. As my five fellow crew members (four in front of me, one behind) alternated their paddles, we kept the rhythm going as we splashed along on this sunny morning.

What was I doing out here in the Pacific, off the coast of west Maui? Paddling a canoe? If my former high-school P.E. teacher could see baby-boomer me now, she wouldn't believe it.

I could hardly believe it, either. Just moments into our 20-minute, mile-out ride my shoulders ached. But as I reflected on the dynamic crews who have paddled for hours at a stretch, sometimes in challenging sea and weather, I figured I could do it for a short time. I recalled the cautionary pep talk by a crew member as he showed me how to hold a paddle: "This isn't a Disneyland ride."

"It's inclusive — all of us together," Kalai Miller, a serious canoeist from Oahu had added. "You have to have everyone doing his (or her) part." That's called "laulima" — cooperation — in Hawaiian.

Concentrating on successfully paddling 15 strokes before the next "Hut!" was cried out, I was too preoccupied to worry about sharks. Or tipping over as a strong wind suddenly blew the sail, tilting the canoe and splashing ocean spray onto my face.

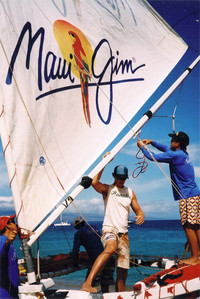

This special single-hulled, six-person, 45-foot sailing canoe can hit 20 knots with a good wind.

Besides surfing, sunbathing and snorkeling, on a special early summer weekend folks can also have free canoe rides in Maui, as I was doing. I was participating in the Wa'a Kiakahi ("wa'a" is canoe in Hawaiian) Community Service Day, which takes place on Maui's Kaanapali Beach during the annual racing season among the islands, April to September.

Sponsored by the Kaanapali Resort Association, this year will mark the 10th annual Wa'a Kiakahi event, which offers free canoe rides to the public — normally around the first weekend in June — given by 60 members (10 crews) of the Hawaiian Sailing Canoe Association, which was formed in 1987. The passion and mission of these outstanding canoeists (from different occupations, with ages ranging from mid-teens to 60s) is "to learn, revive, educate and practice those ancient Hawaiian skills and values as they relate to sailing canoes and the Hawaiian culture." The races begin on the Big Island, stop on Maui, Molokai and Oahu, and end in Kauai. Prior to this stop they had started in Keokea on the Big Island, then raced to Hana — then Kahului — both also stops on Maui — before coming here.

The three-day weekend event on Kaanapali Beach kicks off when the crews arrive with a traditional Hawaiian welcoming ceremony.

At 3 p.m. on Friday, the first day, I joined a beach crowd to watch a dramatic "ha'a" (statement of arrival) performed by the elders of Pa Kui a Holo, a school of Hawaiian ceremony protocol. With strong moves on the sand and chanting shouts, they told who they were, where they were from and why they came. Then they asked for acceptance, and announced that they came in peace from the other islands.

Then Hawaiian Cultural Practitioner Clifford Naeole, wearing traditional Hawaiian garb, greeted the elders. He offered a "pule" (prayer) as he chanted to the crew members, watched by bathing-suit clad tourists who solemnly stood holding hands.

"You're becoming partners with nature — catching the wind, knowing the current," Naeole said. "You don't run the rules of the ocean, you are the servant. This practice is a way of continuing the spirituality so our ancestors can smile and say, 'This is done.' Thank you for carrying on the tradition. Respect nature, respect yourself, keep the practice alive, keep yourself healthy."

Earlier he had noted, "Although today most wa'a are made of composite graphite or fiberglass, they are still considered to be living entities by the Hawaiian people. This practice (Wa'a Kiakahi) is a way of continuing the awareness and spirituality of the canoe. Having new technology is great, but the ancient heart and soul of the canoe remains. They may be more refined and faster today, but they keep to the heart of the tradition."

"This is an opportunity to get people to touch the culture," explained Shelley Kekuna, executive director of the Kaanapali Resort Association. "The watermen and women (10 percent to 15 percent are female) are remarkable in their endurance, passion and dedication to keeping this ancient form of transportation alive."

Day Two, on Saturday, encompassed the free canoe rides and "Talk Story" — the verbal tradition relating the history — with several crew members. Tourists and locals, including excited children, lined up near the colorful beached canoes for "first come, first served" rides.

"Very few people in the world have an opportunity to do this," noted Miller, who pointed out that this type of sport that involves surfing, paddling, steering, sailing and reading the water "ultimately requires a diverse skill set."

"This group is bonded," he added. "There's still that cultural aspect; if we can share this experience it's a big part of our lives. What's cool about this is that we have representation from all the islands." (Supported by sponsors, crew members take time off their regular jobs to participate in this expensive sport tradition.)

"Once we leave terra firma it's on — we love to see how fast these things can go, you paddle your hardest," said Miller. "You have to be ready to paddle for four hours if you have to.

"Imagine what it would be like to build a canoe in the old days — no chain saw," he continued. "The canoe was used for transportation, to fish, do battle, explore new lands, integral to the survival of you and your family." Miller also pointed out that "today we can't get to the corner store without a GPS" — reminding us how the ancient Polynesians navigated by the stars.

"We're really competitive but also very good friends," added Marvin Otsuji of Kauai, pointing out that sometimes hours-long races can be won within seconds. And yet if a crew is in trouble, others will stop to help.

On Sunday morning — the last day of Wa'a Kiakahi — I arrived at 7:30 back on the windy beach for that day's canoe departure ceremony. The canoes would race to nearby Molokai, the next leg.

As the tanned and sunburned tourists and locals surround them, Naeole gave a farewell blessing to the crew with water from a wooden bowl and ti leaves. As they stood solemn, well-wishers gathered on the beach remained respectfully silent.

"The sailing canoe became a symbol of the Hawaiian renaissance — a symbol of pride, of accomplishment, being able to love and know your environment," summed up Miller. "We're proud to perpetuate this culture."

WHEN YOU GO

For more information, visit www.hsca.info, www.kaanapaliresort.com and www.gohawaii.com/maui.

(SET CAPTION) Cultural practitioner Clifford Naeole greets the elders of Pa Kui a Holo as they perform a dramatic "ha'a" (statement of arrival) during Hawaii's annual Wa'a Kiakahi event. Photo courtesy of Sharon Whitley Larsen. (END CAPTION)

Sharon Whitley Larsen is a freelance writer. To read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com.

View Comments