By Sharon Whitley Larsen

"You must visit the Sixth Floor Museum!"

That's what I always tell friends who are headed to Dallas. On both of my visits I was so moved reliving those dark days of Nov. 22-25, 1963, starting with President John F. Kennedy's assassination and ending with his poignant funeral. Those of us old enough to remember will never forget that weekend, when we sat glued to the television and watched a pivotal moment in history develop before us.

During the recent commemoration of the 50th anniversary of this event several television documentaries aired and numerous new books launched. For those who want to pursue more details and information, however, the Sixth Floor Museum — formerly the Texas School Book Depository, housed in an early 20th-century warehouse on Dealey Plaza — is a great place to start. Visitors are transported to the early 1960s with some 45,000 artifacts — large photos, film footage, recordings, newspaper headlines, amateur home movies, interviews and memorabilia — documenting those days. There are JFK campaign photos and videos; photos of the presidential years; and items covering the visit to Dallas — the worldwide grief response, the investigation, the legacy.

Since it opened in 1989, more than 6 million people from around the world have toured the museum, with some 325,000 visitors annually. In 2002 the seventh floor opened to house special temporary exhibits.

One of the most eerie sights is seeing the actual sixth-floor window where Lee Harvey Oswald allegedly aimed his rifle at the presidential motorcade below on Elm Street. Boxes are stacked near the window to replicate how police found the scene immediately following the assassination.

On my most recent visit, as visitors talked quietly among themselves or listened to the self-guided audio tour, I recalled my link to JFK through a special man: Patrick McMahon. A Navy veteran, he was rescued by JFK on the PT-109 during World War II. Many Americans don't know about their touching friendship, which lasted 20 years.

"I owe it to my Skipper to tell about the PT-109; I owe it to his memory," McMahon told me when we first met in 1983.

He was a retired Cathedral City, Calif. (near Palm Springs), mail carrier — then postmaster — who had moved to Encinitas, Calif., in 1975 with his wife, Rose.

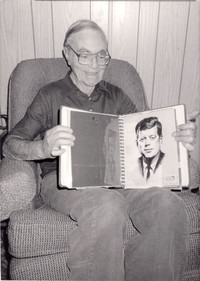

Over the next several years I would visit McMahon in his home to hear his Kennedy anecdotes, browse his photos and memorabilia, and read the numerous hand-written letters that JFK sent to him. McMahon always fondly referred to Kennedy as "the Skipper." They remained friends until that fateful day in November 50 years ago.

McMahon was an automotive repairman in Detroit in 1941 when, at age 37, he enlisted in the Navy. It was in the Solomon Islands that McMahon was assigned to the PT-109, which was commanded by 26-year-old Kennedy.

"I remember when I first met the Skipper I couldn't believe how thin he was. He must have weighed only 135!"

McMahon was assigned to the engine room, and he remembered having to install a replacement engine on one occasion.

"Normally when a new engine had to be put in, the skippers of the other PT boats would be looking over the shoulders of their repairmen and nagging them to hurry. Not my Skipper. He'd peek his head down and call out, 'Mac, call me when she's ready!'

"He had confidence in his men; his crew loved him. He would do anything for anyone."

Shortly past midnight on Aug. 2, 1943, the Japanese destroyer Amagiri rammed the PT-109, slicing it in half and instantly killing two of the 13 crew members. "Immediately I saw a wall of fire coming through the hatch," recalled McMahon, who suffered second- and third-degree burns from which he fully recovered.

The surviving crew decided to swim three miles to a nearby island. McMahon was in terrible pain.

"The Skipper came over to me and said, 'Mac, you and I will go together.'

"I said, 'I'll just keep you back. You go on with the other men — don't worry about me.'

"Exasperated, the Skipper cried out, 'What in the hell are you talking about? Get your butt in the water!'

"The Skipper swam the breaststroke, carrying me on his back, with the leather strap of my kapok clenched between his teeth. It was daylight, and it took about four hours to swim the three miles to the island."

Later they swam to a larger island.

"It took several hours to reach it, and when we finally arrived on the land, the Skipper was physically ill, retching and vomiting. Many of the crewmen were frustrated and despondent. We thought constantly that we'd never be rescued."

JFK ended up spending some 30 hours in the shark-infested water during the ordeal, attempting to attract the attention of another PT boat. At times, showing his humor, Kennedy would say, "We're going to get back if I have to tow this island back!" With the help of some natives, the crew was discovered and rescued several days later.

During McMahon's hospital recuperation, JFK sent a hand-written note to Rose McMahon on Aug. 11, 1943, just days after the rescue, reassuring her of her husband's recovery:

"Your husband — though bothered by a hand injury — is alive and well. ... You can have the satisfaction of knowing that through an extremely hard and trying period your husband acted in a way that has brought him official commendation — and the respect and affection of the officers and crew with whom he served. He will shortly be able to write himself."

Over the next several years, the two corresponded by mail and visited in person. On Jan. 1, 1955, JFK, then a U.S. senator, responded to a note McMahon had sent him regarding his back surgery:

"Dear Mac — Many, many thanks for your very kind message to me when I was in the hospital in New York. Hospitals are gloomy places ... and it makes a tremendous difference when friends remember you as you did."

The McMahons visited the Kennedy compound at Hyannis Port, and McMahon was thrilled to attend the presidential inauguration and parade.

"All the crew rode on the PT-109 float in the parade as a surprise to the Skipper. As we passed by the presidential reviewing stand, Kennedy stood up, grinned, whipped off his silk top hat and gave us the Skipper's signal: 'Wind 'em up, rev 'em up, let's go!'"

He cherished a signed, framed photo of the PT-109 inaugural float: "For Patrick McMahon — with the warm regards of his old skipper — John F. Kennedy."

McMahon would see JFK when he visited Palm Springs. The Secret Service would call him to leave his mail rounds and go to the airport, where he would sit in a limo and wait for the president. The last time he saw his Skipper was in 1961.

"After his plane landed, he sat in the car with me, shook my hand and repeated the same thing that he had said to me often throughout the years, 'If there's anything you ever need, Mac, let me know — it will just take a telephone call.'

"After what he did for me — the president of the United States saved my life — I could never have asked him for anything."

In 1964, Robert Kennedy congratulated McMahon on his promotion to Cathedral City postmaster: "The President was always so fond of you and he would have wanted this for you also."

McMahon died in Encinitas, Calif., in February1990 at age 84.

WHEN YOU GO

The Sixth Floor Museum is open every day except Thanksgiving and Christmas: www.jfk.org.

Dealey Plaza Cell Phone Walking Tour: www.jfk.org/go/visit/cell-phone-tour

John F. Kennedy Memorial Plaza: www.jfk.org/go/about/history-of-the-john-f-kennedy-memorial-plaza

Sharon Whitley Larsen is a freelance writer. To read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com.

View Comments